Last week’s blog talked about creating opportunities in the classroom for good drama, lessening the need for bad drama; this week we begin a series of blogs addressing specific “bad drama” behaviors that commonly occur in classrooms. Over the coming weeks, as we discuss a variety of ways in which children negatively interact with others or with the environment, please contextualize these discussions within the greater truth discussed last week: we humans are hard-wired to be problem-solvers. Drama factors prominently in that tendency; we seek to be the hero in our own story. Absent authentic occasions to be problem solvers and heroes (“good drama”), we humans will create problems to be concerned about (“bad drama”). So, as we discuss how to minimize or eliminate specific bad-drama behaviors, remember that something willbackfill the void left when those behaviors are removed. As guides, we can influence what replaces the negativity. We can invigorate opportunities for good drama within our classrooms – to help our children meet their need for drama in positive ways – or we can let the need run its course, taking the path of least resistance, certain that somethingwill fill that void… With that in mind, let’s turn our attention to one of the ways that children will create drama.

By this point in the year, children have a well-developed sense of what is clearly acceptable and clearly unacceptable in the classroom and in the school. Some gray areas remain (and always will), but for the most part, children are happy to stay within the bounds of known acceptable behavior.

And then a child comes to report that someone elsehas done something wrong. And another. And another.

The nature of the report is a little different at different ages. Younger children will report incidents from the mildly questionable to the clearly unacceptable, often at least in part to clarify whether the action is ok or not; “Chloe is painting without a mat under her work!” Older children will usually report only on things that affect them personally; “Chad and Enrique have been at snack for 25 minutes! (…and I am next on the snack list…)” or “Rosalinda took my pencil.” Here, the goal of the reporting child is most often to seek adult intervention.

At times, teachers can feel overwhelmed by children reporting one another’s offenses. This can be compounded when children subsequently accuse each other of tattling, thus amping-up the drama.

As with anything that repeatedly disturbs an authentic, peaceful, productive work environment, we look first to ourselves and to the environment that we created for possible solutions. In this case, we ask ourselves if children clearly understand the difference between someone tattling and someone getting help with something that is authentically beyond his/her ability to fix. This distinction can be drawn for the children in (no big surprise) a Grace and Courtesy lesson. We want children to know that tattling is reporting what someone else is doing with the intention of “getting them in trouble”. This is never acceptable because it is harmful to the community. Getting help to solve a problem, however, is always acceptable and often admirable. How can we tell the difference? When we are tempted to tell someone in authority, we ask ourselves how we would feel if a friend was able to help us solve our problem. If we would be happy and content, then we can rest assured that we are not motivated to get the person “in trouble”. We can further assure ourselves that we are doing the right thing if we truly try to get help with the situation without naming names. “I am having a hard time because someone is keeping materials out that they aren’t using.” Reinforce the point with a couple of skits illustrating the difference, and you have established a strong foundation. For bonus points, include a discussion of gossip. Gossip is talking about someone behind their back with the intention of making others think less of that person. It is tattling’s more dangerous cousin; both create a negative event, bad feelings, and ill-will, but tattling is self-limiting, while gossip is self-perpetuating. Gossip heard is usually gossip passed on to another, creating an endless supply of drama.

Having laid the foundation through the Grace and Courtesy lesson, we build on that foundation every time we respond to a child reporting another’s activity. Will we respond by becoming the hero of the story or by empowering the child to be the hero?

In the case of Chloe, if we glance over and see that in fact she does have a paper on the rug and is painting on the paper without a placemat to protect the rug, our initial impulse might be to walk (possibly briskly) over to Chloe and ask her to put a mat under her work. From the adult perspective, this protects the rug and satisfies the reporting child. Mission accomplished. But let’s consider this from the reporting child’s (Esmeralda’s) perspective. If all Esmeralda was seeking was confirmation that this behavior was not ok, we have overstepped. Esmeralda learns that when she reports something, it can get the other person “in trouble”. Seeing this might engender feelings either of guilt or of power. If Chloe sees Esmeralda reporting the situation to an adult, Chloe may accuse Esmeralda of tattling, which will almost assuredly ensure a future opportunity to practice conflict resolution between the two students.

A better solution empowers child who reports the situation to gently and non-judgmentally correct the problem. This is harder than it sounds, because we have to intentionally turn off our own natural tendency to be the problem-solver. We have to cast ourselves in the role of observer and coach rather than judge, jury, and executioner.

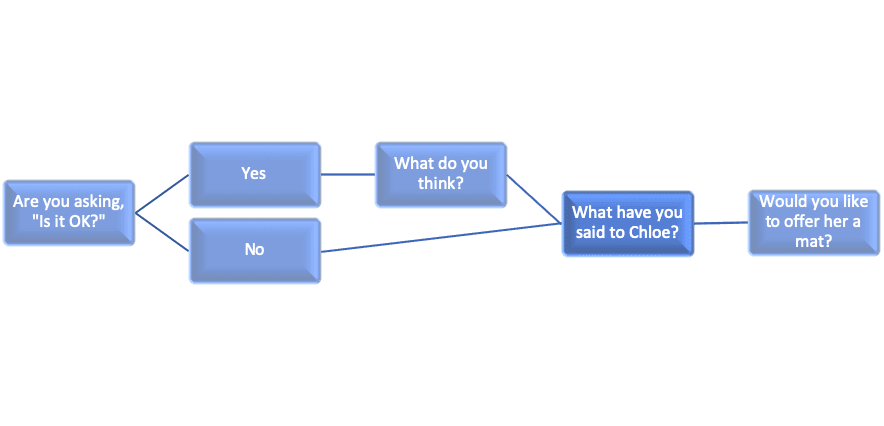

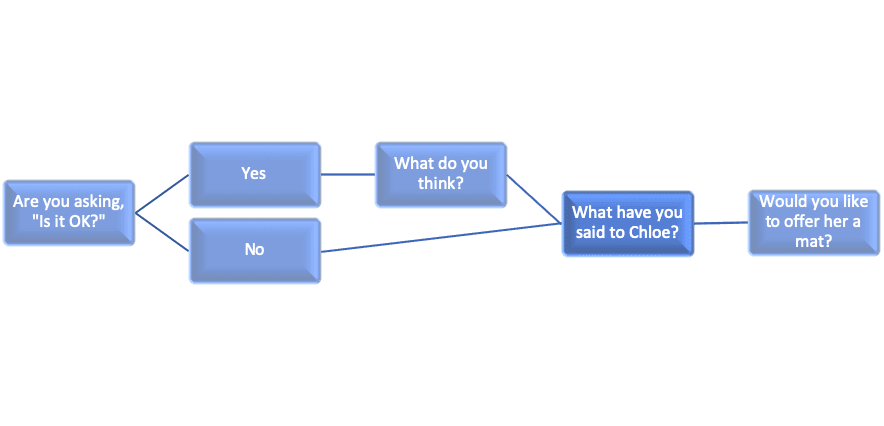

In this example, we can begin by asking Esmeralda non-judgmentally, “Are you asking me if that is ok with me?” (Important: Invoke a pregnant pause -wait for Esmeralda to answer!)

- If Esmeralda says yes, guide her to decide whether or not shethinks the behavior is acceptable. “What do you think? What could happen if someone paints without a mat?” (If Esmeraldadecides it is not a problem after all, that the behavior is ok, she will go on about her business and, once she is no longer focused on Chloe, you can take a placemat over to Chloe and ask her to put it under her paper. If Esmeraldadecides that the behavior is a problem, she likely will have reasoned through why it is a problem. This valuable step empowers her to reason through future incidents more confidently, hopefully without adult assistance.)

- If Esmeralda says that she is not asking if the behavior is ok with you, if she says that she knows the behavior is not OK, she will likely tell you what is inappropriate about the behavior.

In either case, if you agree that the behavior is problematic, confirm her thoughts on why the behavior is unacceptable by nodding knowingly, followed by another pregnant pause.

If Esmeralda continues to await your action or pronouncement, you know that she is seeking more than just confirmation of what is acceptable or unacceptable. She wants you to intervene. This might be because she authentically needs help to solve the problem or it might be that she simply wants to “get Chloe in trouble.” Is she seeking help to avoid harm to the environment or is she tattling? Thankfully, we don’t have to decide which it is! We promote the former and discourage the latter at the same time when we empower a child to kindly and non-judgmentally solve the problem; we remove our adult-power and our need to judge from the equation.

Since we believe that all members of the class are equally responsible for maintaining a peaceful working environment, not just the adults, we ask what the childhas already said or done to solve the problem. We follow that up with asking what the child thinks should be done next. Here is one way that might play out:

- Ask Esmeralda what she has said to Chloe about using a mat.

- Esmeralda reports that she has said nothing so far (the most common response).

- Ask Esmeralda to imagine that she is the one painting without a mat, and ask her how she would prefer to be reminded.

- If needed, guide Esmeralda to a gracious approach like handing a mat to Chloe saying, “I noticed that you didn’t have a mat and I thought you might like one.” Help Esmeralda see that I-statements are less accusatory and less judgmental than you-statements like, “You are supposed to have a mat under your painting.” When people don’t feel judged, it is easier for them to accept help.

At this point, it is important to use your knowledge of your children in deciding the next step. Ideally, we want Esmeralda to be the one to approach Chloe. It is the option that most empowers Esmeralda. It is less likely to make Chloe feel as though she is “in trouble”, and therefore less likely to result in repercussions for Esmeralda. It reinforces the notion that we are allequally responsible for maintaining a positive, supportive work environment. And a successful interaction will help Esmeralda to be braver, more confident, and more skillful when self-advocating in the future. If, however, we know that there is a history of bad blood between the two children, if Chloe is going through a particularly rough patch or is likely to respond to the suggestion negatively, or if Esmeralda is highly sensitive to negativity from peers, we might refrain from having her speak to Chloe. We might send her back to her work space and ask her to observe while you say the same words to Chloe that Esmeralda helped choose, “I noticed that you didn’t have a mat and I thought you might like one.” In all probability, Chloe will accept the mat; you can go back to Esmeralda and talk about how that might feel if she were to approach Chloe or another child in the same manner “next time”. If Esmeralda’s true goal was to get Chloe in trouble, your positive interaction with Chloe will not feed that mistaken goal, and your teachable moment with Esmeralda will show her that the expectation is that ultimately, we go directly to the person that is causing our distress without involving a middle-man.

On the other hand, if Esmeralda is feeling brave enough to approach Chloe, it is important for Esmeralda to know that if Chloe declines the mat, that’s ok – it is not Esmeralda’s job to get Chloe to use a mat. She can just say, “OK” and put the mat away. Should that actually happen, the best recourse is to find a way to solve the problem without involving Esmeralda, such as by calling Chloe to a lesson or asking her to help you with a particular task. The issue of the missing mat can be addressed with a reminder as Chloe returns to her work and/or as a group reminder at the next class meeting.

Does this take longer than walking (possibly briskly) over to Chloe and asking her to put a mat under her work? Yes, it does. But it might not take as long as you fear – probably less time than it took you to read the above description of how the incident might unfold! If this method took even 5 minutes and, in the process a child learns how to advocate for the environment, for another child, or for him/herself, is it worth it? If it means that you would have fewer occasions of children reporting one another’s behaviors throughout the day (a.k.a. a more normalized classroom) is it worth it? I hope so!

When the details are stripped out, it really is a very simple process:

Let’s look at another example, with the child’s words in italics:

- “Chad and Enrique have been at snack for 25 minutes!”

- “It sounds like you aren’t ok with that. Are you asking me if that is ok with me?”

- “No – I know it’s not ok. Snack is supposed to be 10 minutes. And I am really, really hungry!”

- (Nod in affirmation…)

- “What have you said to Chad and Enrique so far?”

- “I told them that they had to leave, that their time was up … and they totallyignored me!”

- “So, what do you suggest?”

- “I think you should kick them off of snack.”

- “Well, I could do that, but there might be a way for you to stay in charge of the situation, a way that would get your turn at snack without needing an adult to get it for you. Let’s think about this. If you were Enrique or Chad, and you knew that your time was up at snack, how would you like to be asked to make space for the next people?”

- “I use the timer so that I don’t go past 10 minutes.”

- “OK, but if you forgot to set the timer, how would you like to be asked to make space for the next people?”

- “Well, I don’t know. Maybe if someone said, ‘I think your time might be up’…”

- “That is a nice way to remind someone that others are waiting. Here’s some others: ‘I notice that the timer isn’t running any more. Did you forget to set it or has it gone off?’ Or, ‘I am next for snack – can you tell me how soon you will be done?’ Or there is always the non-verbal reminder: go get your snack and sit patiently nearby the snack table – close enough that they can see you – until they realize that their time is up. Do any of those appeal to you?”

- “I think I will go get my snack and wait.”

- “Patiently?”

- “…OK”

(At this point, it may be wise to tip the scales in favor of the child waiting for snack by busying yourself with a task near the snack table. Your presence may bring out more charitable actions on all sides of the issue. After the child and his/her friend have had snack OR as a grace and courtesy lesson a day or two later, consider discussing ways to ask for what you need, including a skit showing a method that puts people immediately on the defensive and the alternative, which usually involves more asking and less telling/bossing.)

The snack dialog takes about 2 minutes – probably no longer than it would take if you were to “solve the problem” yourself by talking to the children currently at snack about their perception of how long they had been at the table – and helps the hungry child learn a better way to ask for what he wants without promoting further confrontation and drama.Sidebar: elementary-age children are very capable of seeing things from other people’s perspectives when prompted but generally they will not naturally think that way on their own. In the heat of the moment, this skill is even less accessible. A great line-time activity is watching the YouTube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ahg6qcgoay4 (no spoilers here) as an illustration of how we all miss what we aren’t watching for. Extend this idea to a situation where someone who is doing something that we wish she wasn’t or not doing something that we wish he were. What aren’t we seeing? How does the situation seem to the other person? When we can see things from others’ point of view, we may or may not be so determined that they change. If we still think that they need to change, we can approach them with empathy, which may increase their ability to listen to what we say. BONUS: Take a scene from a book being read in lit group or in read-aloud. Ask volunteers to describe what happened in the scene from different character’s perspectives. EXTRA BONUS: Persuasive writing perfectly applies seeing a situation from the other person’s perspective! If children are writing to persuade parents to go to a friend’s house or to increase their allowance, their best arguments will not come from showing an understanding of the parents’ point of view. The same is true of advertising!

A Good-Drama Antidote: One way to combat tattling is to institute tootling: telling about someone who is doing something well or special. Some will dedicate a section of wall or bulletin board for children to post when they see or hear something that is good, kind, courageous, strong, generous, smart, or in some way positive. Posts may not name names and must be anonymous. To double-dip into character education, have the children label the post with the trait they most admire. For example, a child might write, KIND: Someone helped me feel better when I was sad.

Reflection for adults(choose one or both)

- How often do children come to me or another adult in the room to report on one another? If it is infrequent, is that because there are few incidents to report or because they fear retribution? If the latter, what would encourage children to self-advocate? A classroom paradigm shift? More group problem solving? Placing a HELP box in the room for children to anonymously make me aware of problems that are currently going underground?

- What is my initial reaction when a child reports on another child? Am I irritated at the interruption? Am I inclined to quickly solve the problem, to be the hero of the situation? If so, what can I do to establish a new habit of coaching children to solve their own problems.

Reflection for children: Please think about recent time(s) when you have been frustrated with a person or situation.

- Were you able to talk directly to the person or people who are at the center of your frustration?

- If so, how did it go?

- If not, what held you back?

- Thinking about the issue or situation now, can you see it from the other’s point of view? How might they have seen the situation differently?

- If you were able to see their point of view at the time, would it have changed how you felt?

Children who can’t recall a recent time when they felt frustrated with a person or situation can answer these questions reflecting on a time when a friend felt greatly frustrated with another.

“If you propose to speak, always ask yourself, is it true, is it necessary, is it kind?”

Socrates